How are games like The Last of Us, Shadow of the Colossus, and Celeste consistently hailed as pinnacle achievements for their respective genres and audiences? They found and embodied the core experience their developers were attempting to create without adding superfluous content that misdirects and obscures that vision.

In Jesse Schell’s game design textbook, The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, he emphasizes that a game is not just a medium for entertainment but a powerful tool for evoking emotions. Understanding and conveying these emotions is the key to creating a truly immersive experience. This philosophy is so crucial that he dedicates his first two lenses to it: The Lens of Emotion and The Lens of Essential Experience. These lenses are tools and gateways to a deeper understanding of game design.

Lens #1: The Lens of Emotion

People may forget what you said, but they’ll never forget how you made them feel. - Maya Angelou

To make sure the emotions you create are the right ones, ask yourself these questions:

- What emotions would I like my player to experience? Why?

- What emotions are players (including me) having when they play now? Why?

- How can I bridge the gap between the emotions players are having and the emotions I’d like them to have?

Lens #2: The Lens of Essential Experience

To use this lens, you stop thinking about your game and start thinking about the experience of the player. Ask yourself these questions:

- What experience do I want the player to have?

- What is essential to that experience?

- How can my game capture that essence?

Let’s look at some games whose creators are masters of establishing and sticking to their intended essential experience. This blog will look at Shadow of the Colossus, The Last of Us, and Celeste. These games exemplify the importance of knowing and building for the essential experience and cutting away all content that is purely additive and can cause an experience to bloat.

Shadow of the colossus

One of the most significant and extreme examples of a game built around its essential experience is Team Ico and Fumito Ueda’s masterpiece Shadow of the Colossus (SotC). A game about loneliness, desperation, and overcoming impossible odds, SotC is a minimalist game that prioritized removing all content that didn’t directly add to the intended experience. Game designer and professor at the USC School of Cinematic Arts Andy Nealen breaks down the minimalist design approach:

“Minimalism allows a designer to have a strong vision, but not describe it in every single detail, thus leaving the player to explore the elements, their connections, and their dynamical meaning. It also means only leaving the best parts in the design: If one part is better than the others, the others become a liability, and need to be removed or radically improved. The best designs and design processes I have witnessed have a ‘cutting floor’ that is ten times the size of the final game.” - Andy Nealen. [1]

SotC is focused on defeating ancient colossi in the Forbidden Lands. Initially, the game had 40 colossi, then 24, and finally 16. During development Ueda prioritized only adding content of value. As the number of colossi increased, their quality, significance, and memorability individually diminished. This philosophy also held true when Team Ico contemplated adding collectible items and experience points to the game. Even though it was a common system within many games, even games similar in genre and style to the one they were creating, Ueda found that many of the possible mechanics would directly conflict with the experience he and his team were trying to develop.

“When I’m deciding whether or not to put something in the game, I’m always looking for meaning behind it, no matter what. Like, does it make sense to put smaller enemies in the game just so you can get items and experience points? I wouldn’t have been able to forgive myself if I’d had a Colossus you wouldn’t be able to beat without some item you’d get defeating smaller enemies. I had the idea of being able to warp through the use of an item, for example, but the huge field would have become pointless. There are two ideas central to the game: Colossi you have to climb and defeat, and an enormous field. I think that once we kept the overall consistency in mind, it was inevitable that the game would turn out like this.” - Fumito Ueda [1]

While these extreme pruning levels are not always necessary, their benefits are worth noting. Everything in SotC has meaning unless intentionally left to be a mystery, the gameplay loop is tight, each Colossus and its respective arena are unique, and the game can be completed before the experience becomes drawn out. All of these benefits ensure that the essential experience of the game is not obscured by any content that does not directly uphold it.

“I have the tendency to ask myself whether or not something makes sense and whether or not it’s elegant in terms of game design. Like pruning tree branches, it’s necessary to cut things out in order to improve the quality of a game.” - Fumito Ueda [1]

The Last of Us

Neil Druckmann is a man who prioritizes making deep and meaningful entertainment experiences. One of his most outstanding achievements, The Last of Us, has earned countless awards and has been one of the greatest pieces of interactive media ever created. A tool that Druckmann uses when creating his narrative and beats, especially while developing The Last of Us, is a minimalist design approach that is not so different from Ueda’s. In an interview with GameSpot, Druckmann breaks down this view while describing the films that inspired him.

“[on No Country For Old Men]… if you want to get something out of this story you have to be engaged with it, you can’t just have it spoon feed you everything because those are the stories that we like so let’s do our best to create that kind of experience, which means we’re constantly asking ourselves “okay, what is this moment really about? What’s the least we have to say or do to kind of convey that, and no more?.” - Neil Druckmann [4]

Druckmann also speaks more directly on his design approach and the reasons for which he follows it in an interview from Boss Fight Books: Shadow of the Colossus by Nick Suttner

“It’s paramount to making something great. It’s easy to come up with a bunch of ideas and just kind of throw them in, and just get the player engaged on that, but to create something elegant… the question I always ask is, ‘What are we trying to convey here and what’s the least we need to do to convey that?’ And we should do no more than that.” - Neil Druckmann [1]

What Druckmann says here is what I believe truly differentiates games that adhere to their essential experiences and tones rather than bloating the game with potentially meaningless content. While games filled to the brim with busy work can keep people playing for longer, the moment-to-moment gameplay becomes less valuable, diminishing the impactfulness of the total experience.

Another important aspect of finding the essential experience in The Last of Us was Druckmann asking himself and his team what type of story they wanted to tell within the intended gameplay frame they were pursuing. They would ask themselves, “Do we need the infected?” but found that by removing them and in place having a plague, the game’s ability to show, and not tell its story became far more difficult. In the end, they determined that since they are making a survival action game, it is paramount to the essential experience of the game to have the players themselves feel as though they are surviving in the world.

“One thing we tried early on to do with the story was say “do we need the infected?”, because we could tell a story about a plague and it’s just about people getting sick and what we found was that then it’s all exposition, like people talking about a disease but I don’t get to experience it, and at the end of the day we’re making a survival action game, so by adding the infected back in you could play what it was like to try to survive this thing.” - Neil Druckmann [4]

celeste

Brought to life from the original Pico-8 game jam submission and created by Maddy Makes Games, Celeste is an indie classic that focuses on tight platforming and an impactful narrative about mental illness and overcoming anxiety. During development, the lead level designer and creative director, Maddy Thorson, devised a scheme for structuring the story and narrative beats throughout the game.

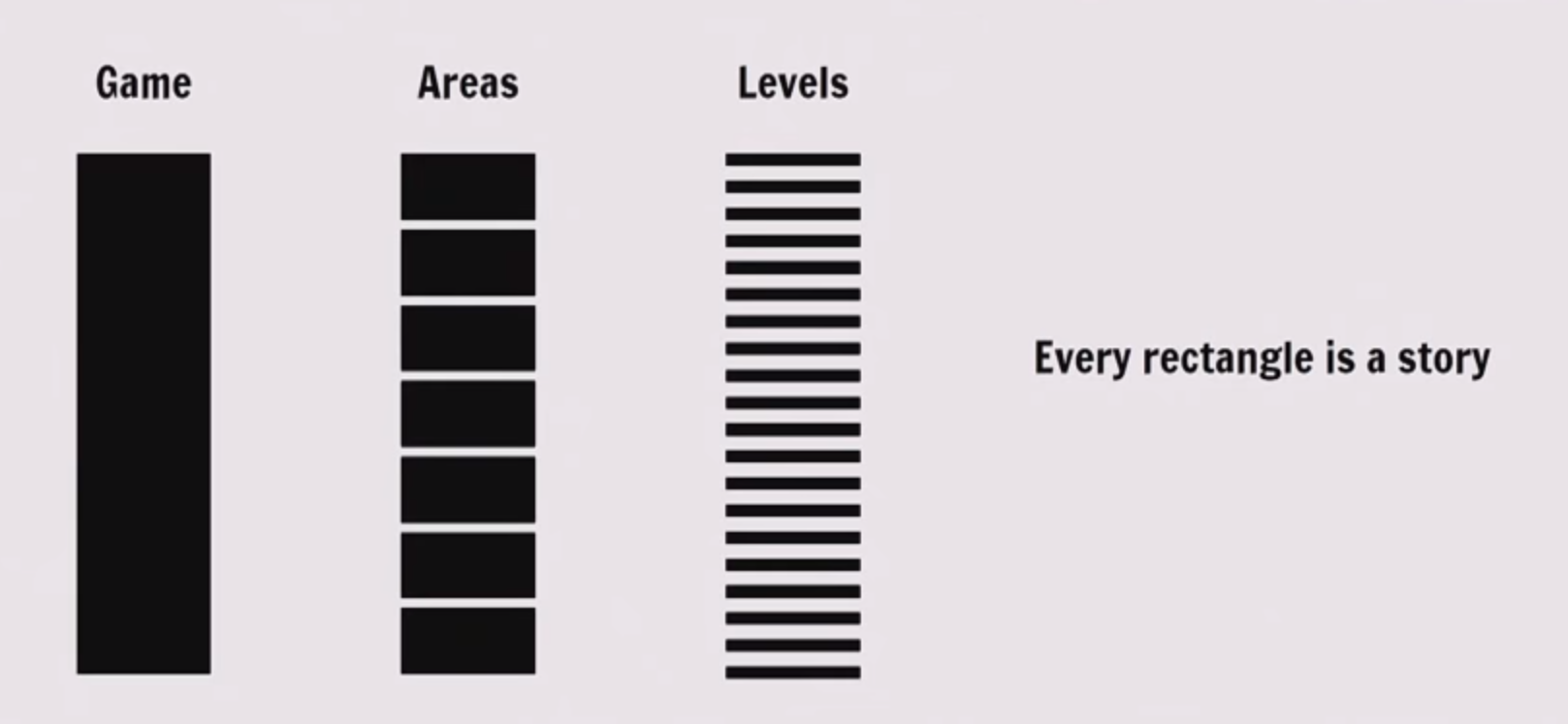

Celeste, a story made up of stories

Game: This is the overall narrative arc for Celeste

Areas: These are the larger sections of the game that propel the story forward and frame the setting of the levels. Each of these Areas contains an arc that determines how Levels flow together.

Levels: These are the individual stages that make up the areas. Every level has a unique story that establishes and upholds the Area’s intended tone.

Celeste's total experience could have featured more than 800 levels, but many will never be seen due to Maddy's dedication to establishing a strong narrative, one of the game's core essentials. During their GDC 2018 Level Design Workshop, Maddy discusses their team's unfortunate necessity to throw out work and start again because a level's tone did not fit into their intended area.

“…nothing came into this game fully formed and we threw out a lot of work. Just last month [January 2018] I threw out 20 levels from our latest area because they just didn’t fit the mood” - Maddy Thorson [2]

Celeste is also a famously challenging game. This difficulty helps players who persist through it connect to the core intended experiences of personal growth, overcoming hardships, and believing in themselves. The game limits player abilities for most of the experience to climbing walls, jumping, and dashing, and this is all you really need to complete the game, not including a few level-specific mechanics. This lean collection of verbs takes a lot of the game's challenge and puts it on the player's abilities. The players themselves must improve in the game to progress, similar to Madeline within the game's narrative.

“Celeste is about traversing space … A central design goal of Celeste was to make character growth walk in step with player growth, so that as Madeline is growing and improving the player is too. Giving you new abilities is a way to fake player growth, but real player growth in this genre comes from mastery and understanding …” - Maddy Thorson [3]